The Shoulder

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body and is surrounded by a number of key soft tissue structures that, not only move the joint, but also hold it in position. The constant demands placed on these structures to achieve both movement and stability make them susceptible to injury. As a result, the majority of shoulder problems are caused by injuries to the ligaments, tendons and muscle. Shoulder problems can affect people of all ages and can be related to general wear and tear, a particular sport or occupation or due to injuries or accidents.

A knowledge of the normal anatomy of the shoulder and its complex arrangement of muscles, ligaments and tendons helps us to understand why a shoulder problem might occur and how to treat it.

Shoulder Anatomy

The shoulder is the most mobile and sophisticated joint in the body.

- The shoulder has global movement, which is extremely important, as it allows us to place our hand into any position in space.

- The shoulder is actually made up of 3 bones linked together by 4 joints that work together as the ‘shoulder girdle’.

- Groups of muscles working in co-ordinated sequence allow the 4 joints of the shoulder girdle to move together.

- The large range of movement potentially makes the shoulder very unstable and liable to dislocate. However, a complex arrangement of soft-tissue structures including

ligaments, muscles and tendons help to keep the shoulder in joint.

The constant demands placed on the ligaments, muscles and tendons to move the shoulder and at the same time to keep it in joint, make them vulnerable to injury. When injuries do occur, because of the intimate relationship between these structures, the problems are often complex and unique to the shoulder.

The Shoulder Anatomy section looks at the shoulder in layers working out from the underlying bones to the capsule and ligaments that surround the joint and then to the overlying muscles and tendons. Seeing how the various structures around the shoulder are arranged and interact helps us to understand how the healthy shoulder works and how the problems from various shoulder injuries and conditions can occur.

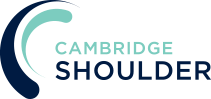

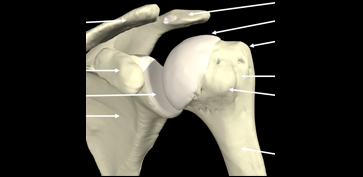

Bones & Joints

The bones of the shoulder are,

- The Humerus - the upper arm bone with the ‘humeral head’ (the ball of the shoulder joint) on the top end

- The Scapula - the shoulder blade. There a number of parts to the scapula.

- the ‘glenoid’ (the socket of the shoulder joint)

- the ‘acromion’ (which covers the top of the glenohumeral joint and attaches the scapula to the clavicle)

- the ‘coracoid’ (a bony ridge at the front of the scapular to which a number of ligaments and muscles attach)

- The Clavicle - the collar bone which connects the acromion part of the scapula to the sternum (the breast bone) ‘strutting’ the shoulder out. This is the only direct bone connection that the shoulder girdle has with the rest of the skeleton.

The joints of the shoulder are,

- The Glenohumeral Joint - formed between the humeral head (ball) and the glenoid (socket).

- The Acromioclavicular Joint – the joint that connects the scapula to the outer end of the clavicle

Find out more about the Acromioclavicular Joint… - The Sternoclavicular Joint- the joint that connects the inner end of the clavicle to sternum. This is the only bony connection between the ‘shoulder girdle’ and the main the skeleton

find out more about the Sternoclavicular Joint… - The Scapulothoracic Joint – this joint involves the movement of the scapula over the ribs at the back of the chest. This is a ‘psuedo’ joint (not a real joint as it does not have any articular cartilage.

Find out more about the Scapulothoracic Joint…

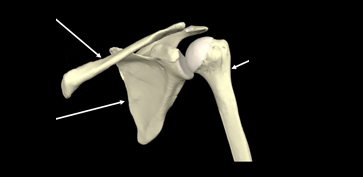

The Glenohumeral Joint is usually referred to as the main shoulder jointand is responsible for the majority of the movements around the shoulder. The ‘ball’ of the Humeral Head is very large in comparison to the very shallow ‘socket’ of the Glenoid. This arrangement allows for the great range of motion of the shoulder joint but, as the socket is so shallow, is potentially very unstable and could dislocate. Fortunately this is not often the case thanks to the complex arrangements of soft tissue structures including the ligaments, muscles and tendons around the shoulder.

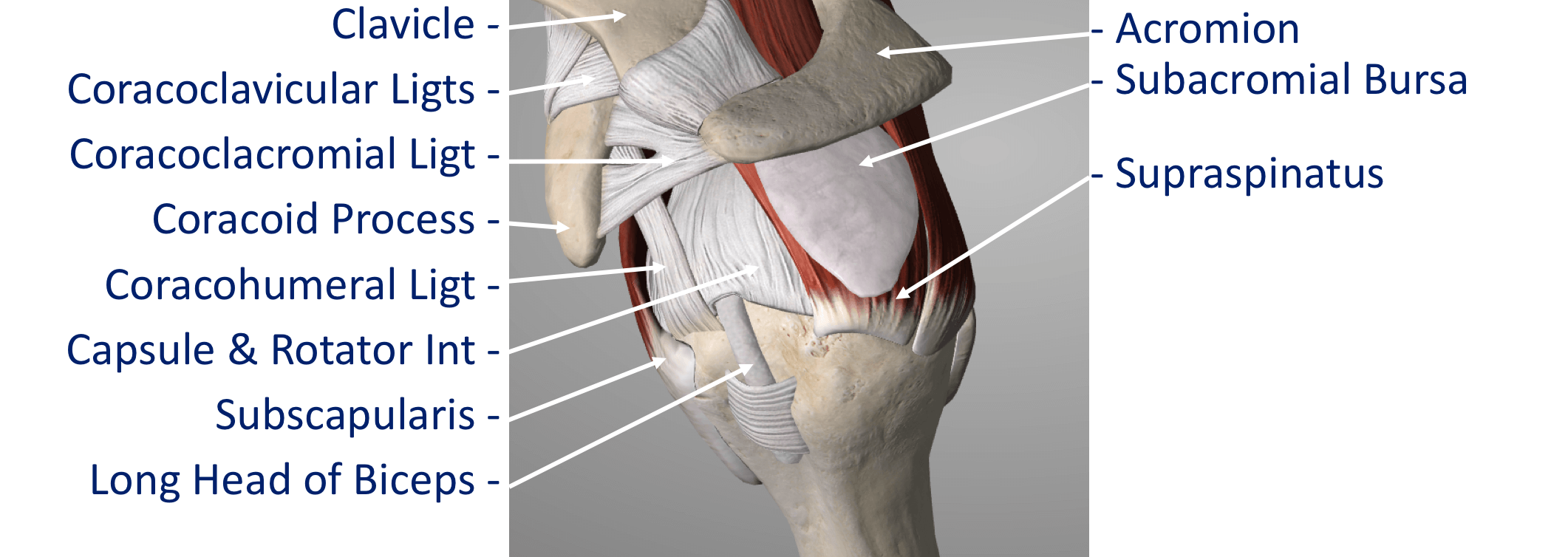

Capsule and Ligaments

There are a number of soft tissue structures around the inner layer of the shoulder whose main function are to help to connect the bones on either side of the joint together. Effectively to keep the shoulder in joint!

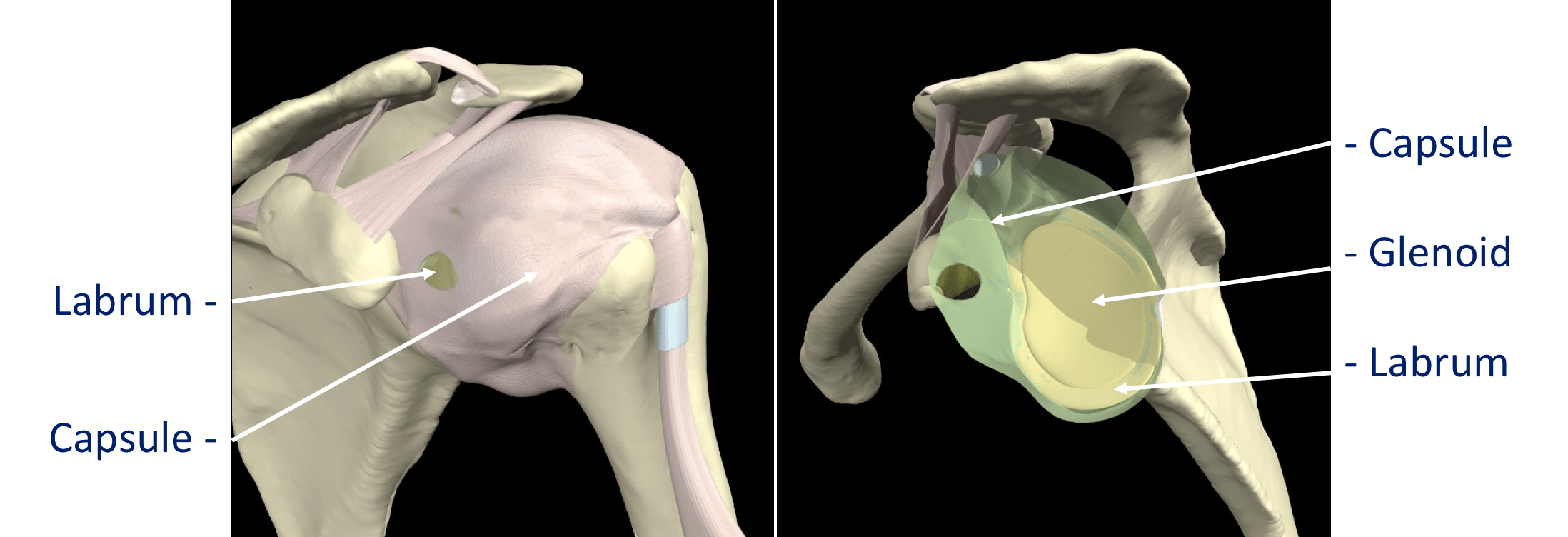

- The Glenoid Labrum – this is a ‘rim’ of tissue that goes around the outer edge of the glenoid, the tendon of the long head of biceps attaches to the top part of the labrum. The labrum effectively deepens the glenoid socket which helps to increase the stability of the humeral head. It works a bit like a ‘chock’ under a wheel preventing the head from ‘rolling’ over the edge.

- The Joint Capsule – this is a watertight sac that surrounds the joint. It is formed circumferentially from around the base of the glenoid socket and passes outwards to join circumferentially around the neck of the humeral head. The inner lining of the sac is covered with synovial tissue which produces synovial fluid that lubricates the joint and provides joint nutrition.

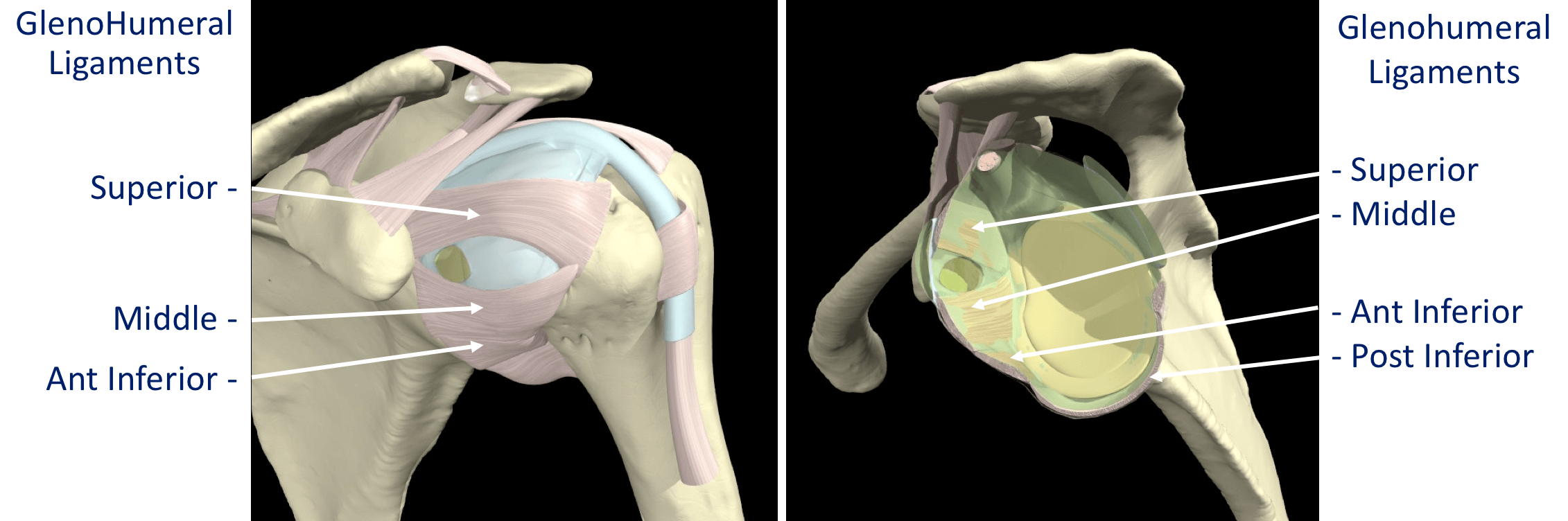

- The Glenohumeral Ligaments (GHL)– within the joint capsule there are 4 strong ligaments that connect the glenoid to the humerus. These are the main structures that keep the shoulder in place and stop it from dislocating. There are 3 ligaments at the front (Superior, Middle & Anterior Inferior Glenohumeral Ligaments) and 1 ligament at the back of the joint (Posterior Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament).

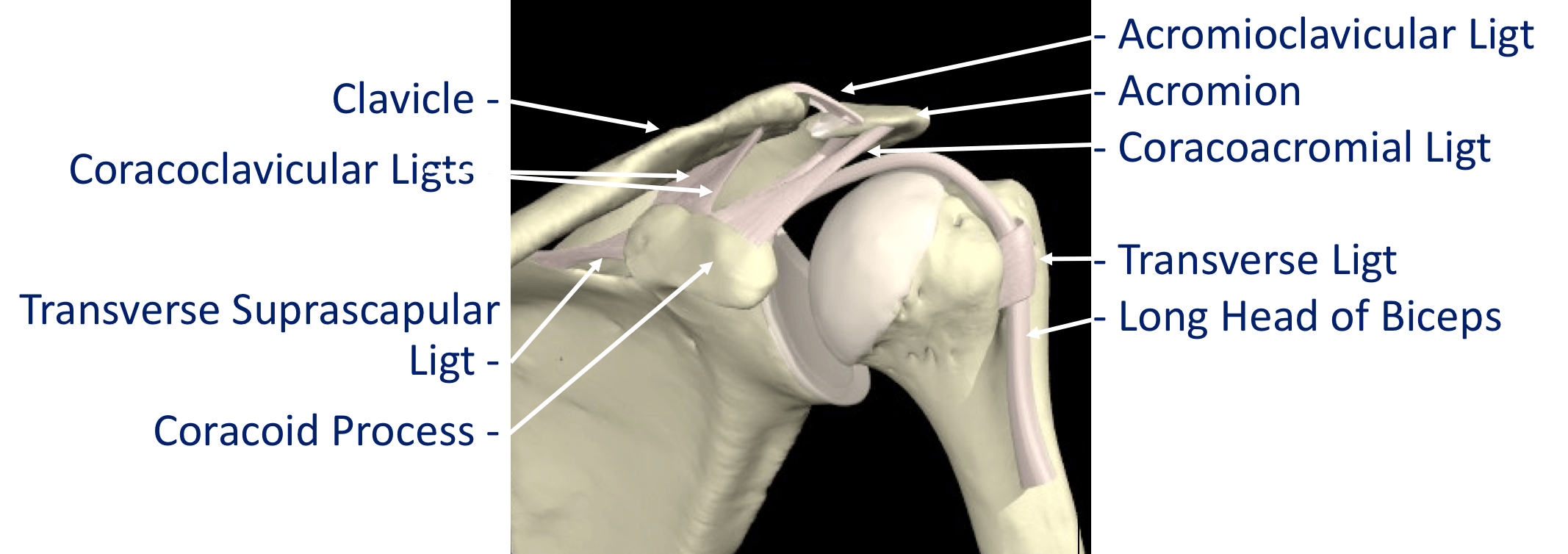

- The CoracoAcromial Ligament (CAL) - this ligament connects the acromion to the coracoid forming a tunnel. The Rotator Cuff tendons pass under this tunnel. In some circumstances the tip of the acromion and the ligament can thicken and cause Impingement to the tendons as they run underneath

- The Acromioclavicular Ligaments (ACL) – these are short ligaments that attach the clavicle to the acromion within the acromioclavicular joint (AC jt)

- The Coracoclavicular Ligaments (CCL) – these are 2 ligaments that connect the clavicle to the coracoid. They help to supply additional stability to the clavicle and the ACjt.

Tendons

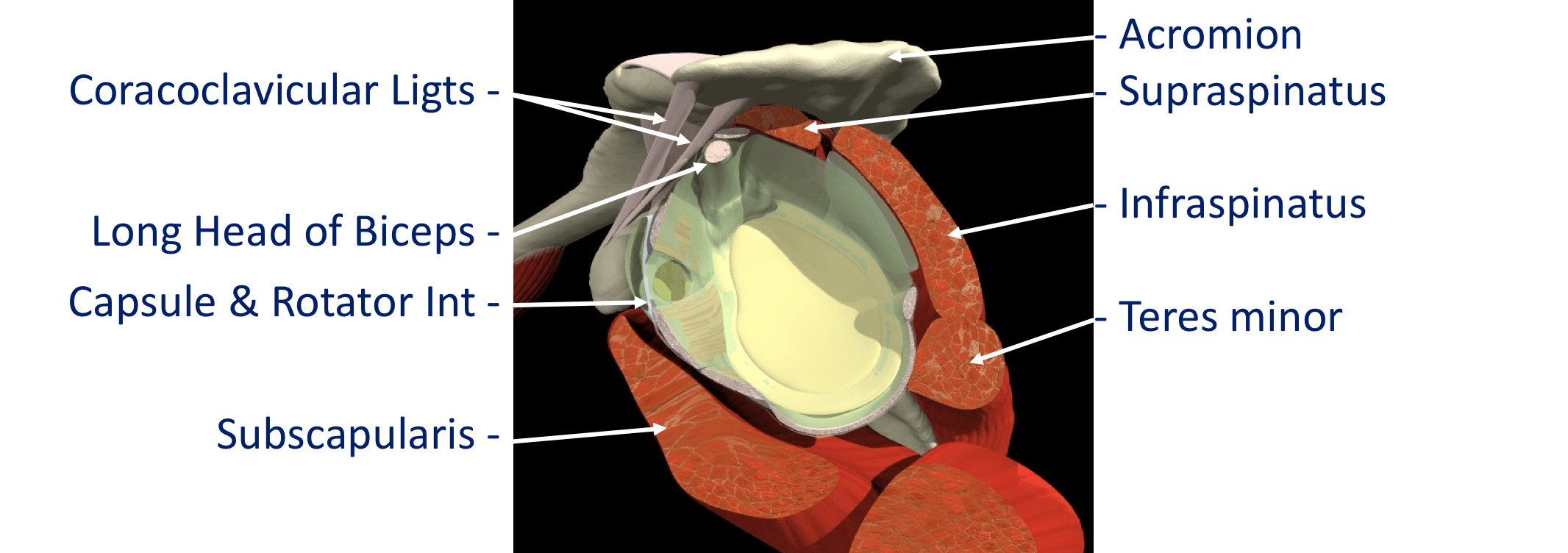

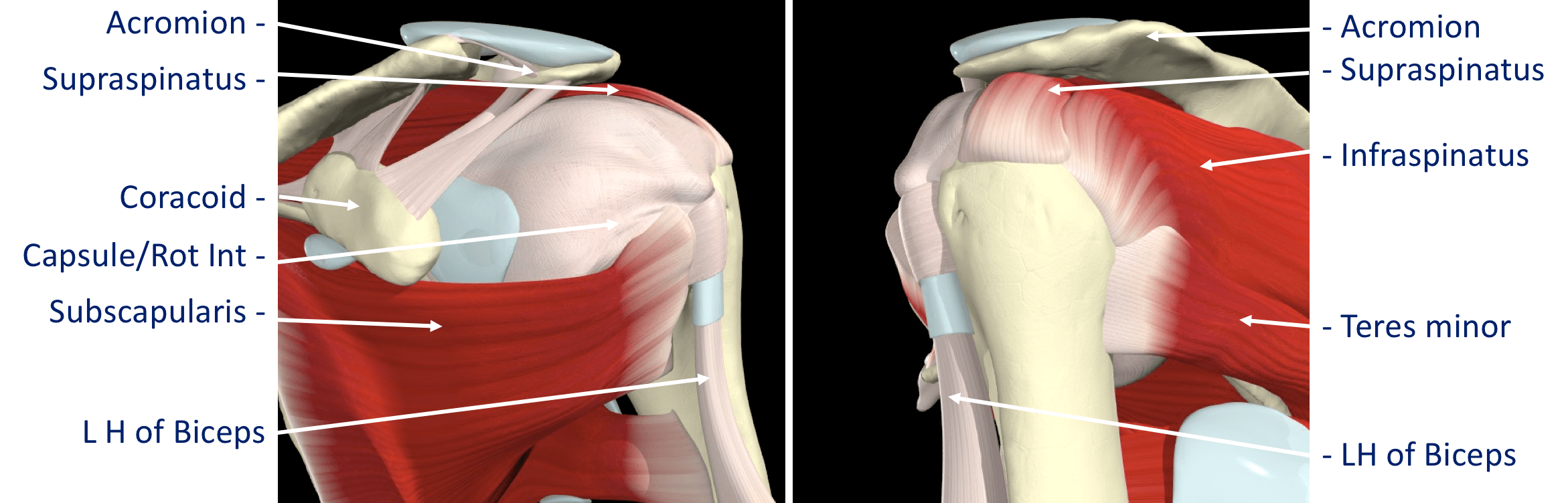

- The Rotator Cuff Tendons – this is formed by a group of 4 tendons that connect the deepest layer of 4 muscles to the humerus. These muscles are,

- Subscapularis

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

- Teres Minor

- The Biceps Tendon – the Biceps muscle, on the front of the arm, is formed from 2 tendons. The Long Head of Biceps tendon begins at the top of the glenoid (with the labrum) and passes out through the shoulder joint to connect to the biceps muscle.

- The Rotator Cuff tendons and the Long Head of Biceps tendon are positioned very close to each other and are often both affected by injury at the same time.

- The Rotator Cuff tendons pass underneath the acromion through the Subacromial Space as they insert into the humerus (Fig 9). The narrow ‘clearance space’ underneath the acromion is the commonest place for Rotator Cuff problems to occur.

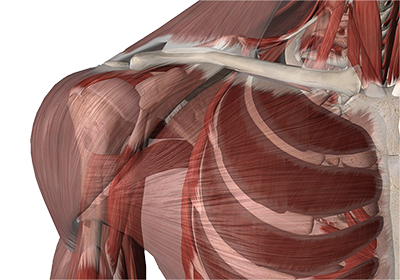

Muscles

There are a large number of muscles around the shoulder which are responsible for moving, stabilising and supporting the shoulder girdle. The muscles can be divided into 3 groups.

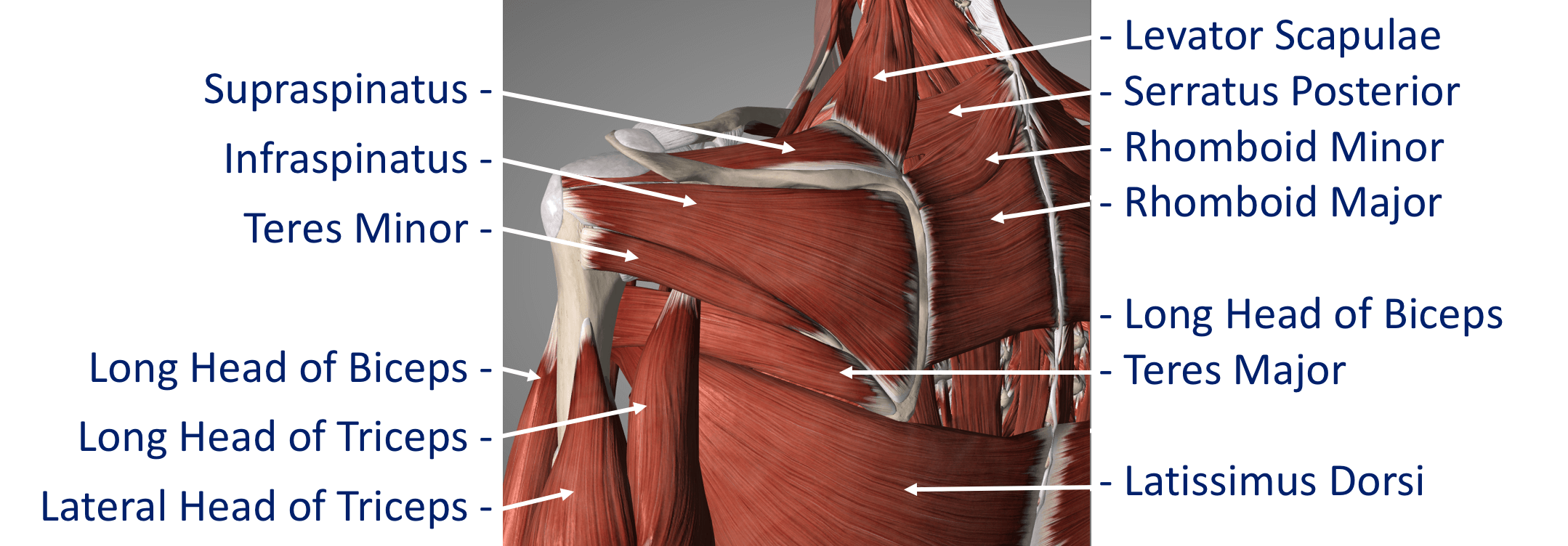

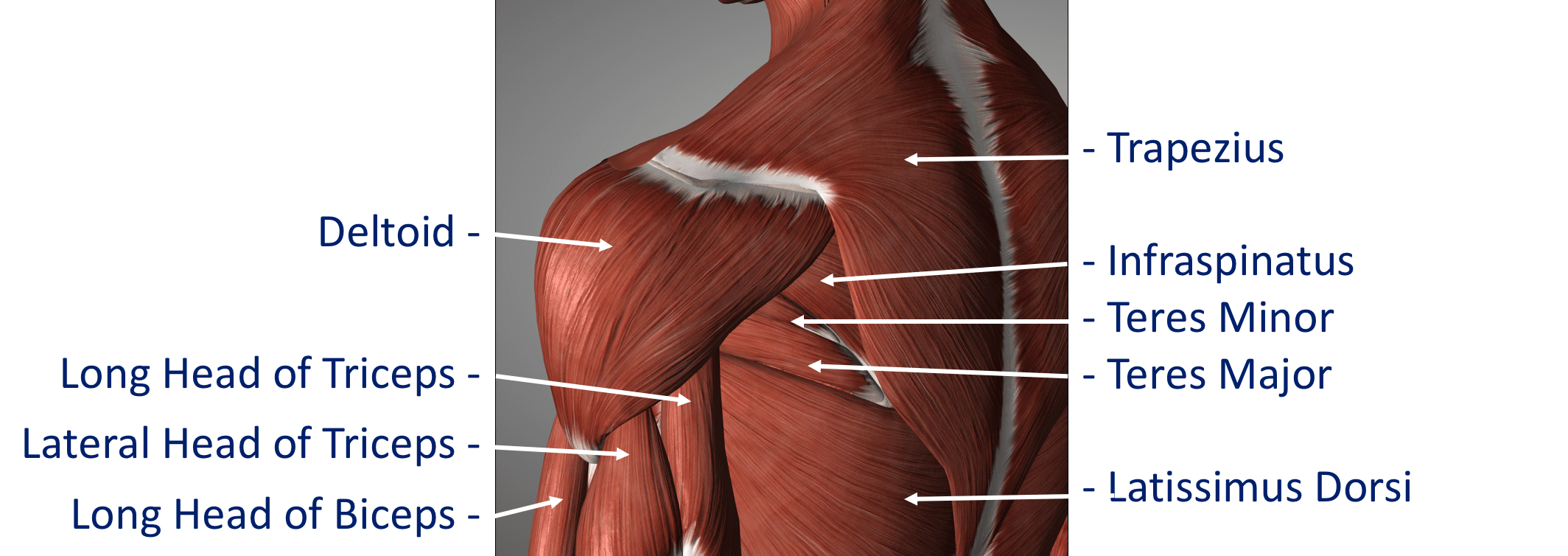

- Deep Muscles (Intrinsic / Rotator Cuff Muscles) – these are the 4 muscles mentioned earlier whose tendons form the rotator cuff. The muscles all arise from the blade (flat surface) of the scapula and pass over the shoulder joint with the tendons attaching onto the humerus.

- Subscapularis

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

- Teres Minor

These muscles often function as a group and are involved in raising, rotating and moving the shoulder in many directions. The combined pull of the Rotator Cuff muscles also pulls the humeral head into the socket of the glenoid helping to stabilise the glenohumeral joint.

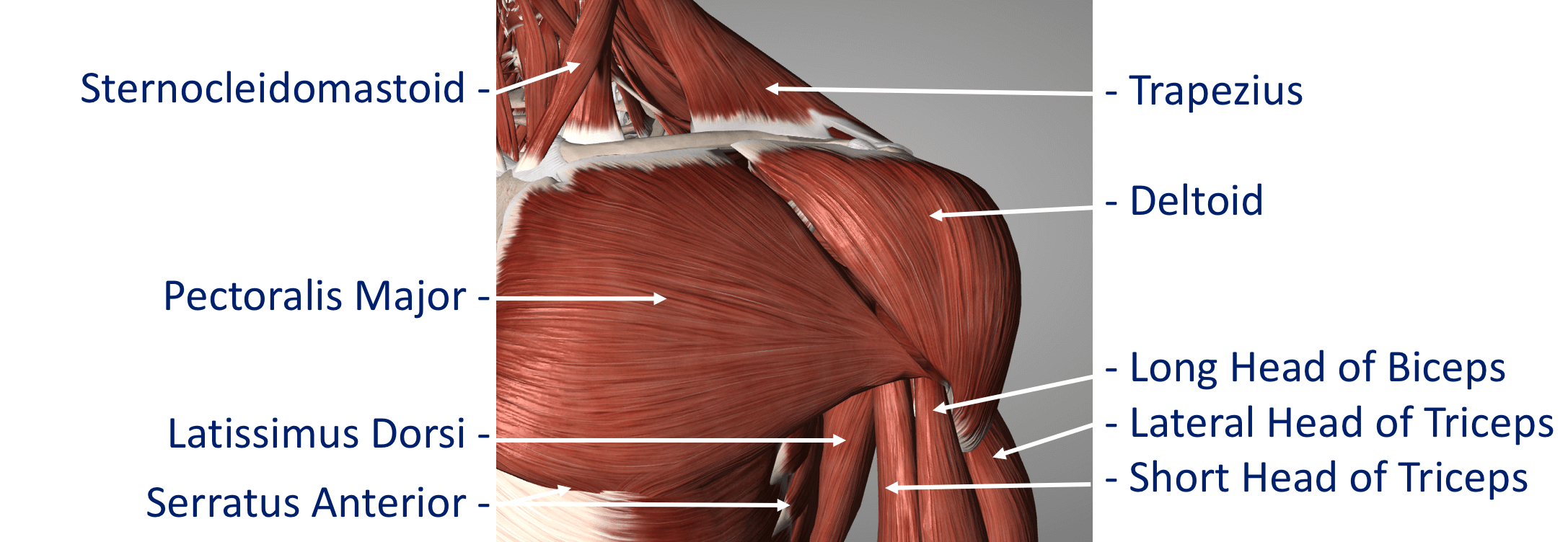

- Intermediate Muscles – These muscles provide additional stability and strength to the glenohumeral joint and the shoulder girdle.

- Superficial Muscles (Extrinsic) – These are the large muscles that can be seen around the shoulder externally and provide strength and powerful movements.

- Deltoid – this is the large muscle over the top and the front of the shoulder which provides the power to lift the shoulder after the rotator cuff muscles have begun the movement

- Pectoralis Major – this is the large muscle over the front of the chest.

- Biceps – this is the powerful muscle over the front of the upper arm that flexes the elbow. One of the Biceps tendons (the Long Head) arise from within the shoulder joint.

Problems can occur with the stability of the Shoulder if the sequential rhythm in which these muscles contract to move the shoulder is disturbed

- Back Muscles (Posterior) – these muscles are involved in suspending the scapula onto the back of the chest wall, stabilising the scapula and moving the scapula over the chest wall (scapulothoracic joint). A number of these muscles, including trapezius, levator scapulae and the rhomboids, originate from the vertebrae of the cervical and thoracic spine.

- Problems can occur with the smooth movement of the scapula over the chest wall if these muscles are weakened or are not working properly.

Bursa

A bursa is a flattened sac that is filled with a very small volume of lubricating fluid. When a bursal sac is placed between 2 structures that move over each other it helps to reduce the friction between them. There are a number of bursae positioned throughout the body between moving structures.

- The Subacromial Bursa – this is a bursal sac that lies between the moving rotator cuff tendons and the undersurface of the acromion that lies above.

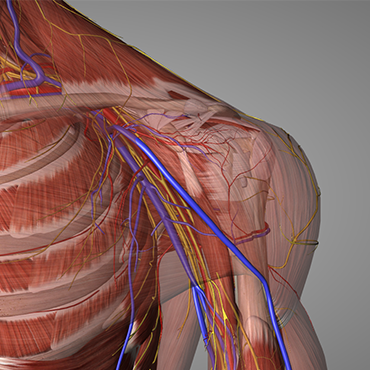

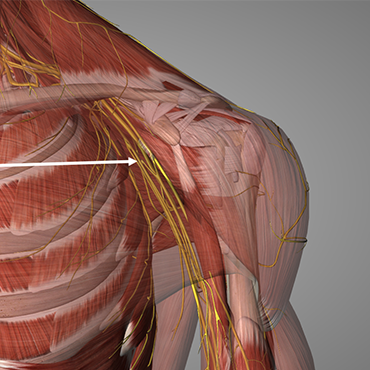

Nerves

Nerves are able to link the brain to specific parts of the body. They carry signals from the brain to move specific muscles and also pass information back to the brain about touch, sensation, temperature and pain. As the spinal nerves which supply the upper limb pass out of the neck they fuse together in a complex arrangement forming the Brachial Plexus.

As the Brachial Plexus passes through the axilla (armpit), underneath the shoulder joint, it divides into individual nerves that supply specific areas of the arm. Three important nerves that supply the shoulder are,

- Axillary Nerve – this supplies power to the Deltoid muscle and feeling to the skin over it

- Musculocutaneous Nerve – this supplies the power to the Biceps muscle.

- Suprascapular Nerve – this supplies power to some of the Rotator Cuff muscles (Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus)

These nerves can be damaged as the result of injury, dislocation or during surgery around the shoulder.

Arteries & Veins

There are multiple intricate arteries and veins that surround and provide the blood supply to all of the structures around the shoulder. These vessels are intimately related to the to the brachial plexus and nerves.